Whitman on Emerson: two approaches to poetry

WHITMAN, WALT, WHITMAN, WALT. Autograph manuscript on Ralph Waldo Emerson

No place, n.d.

One page. 8 x 10 in. Framed with a portrait of Whitman. Very good condition

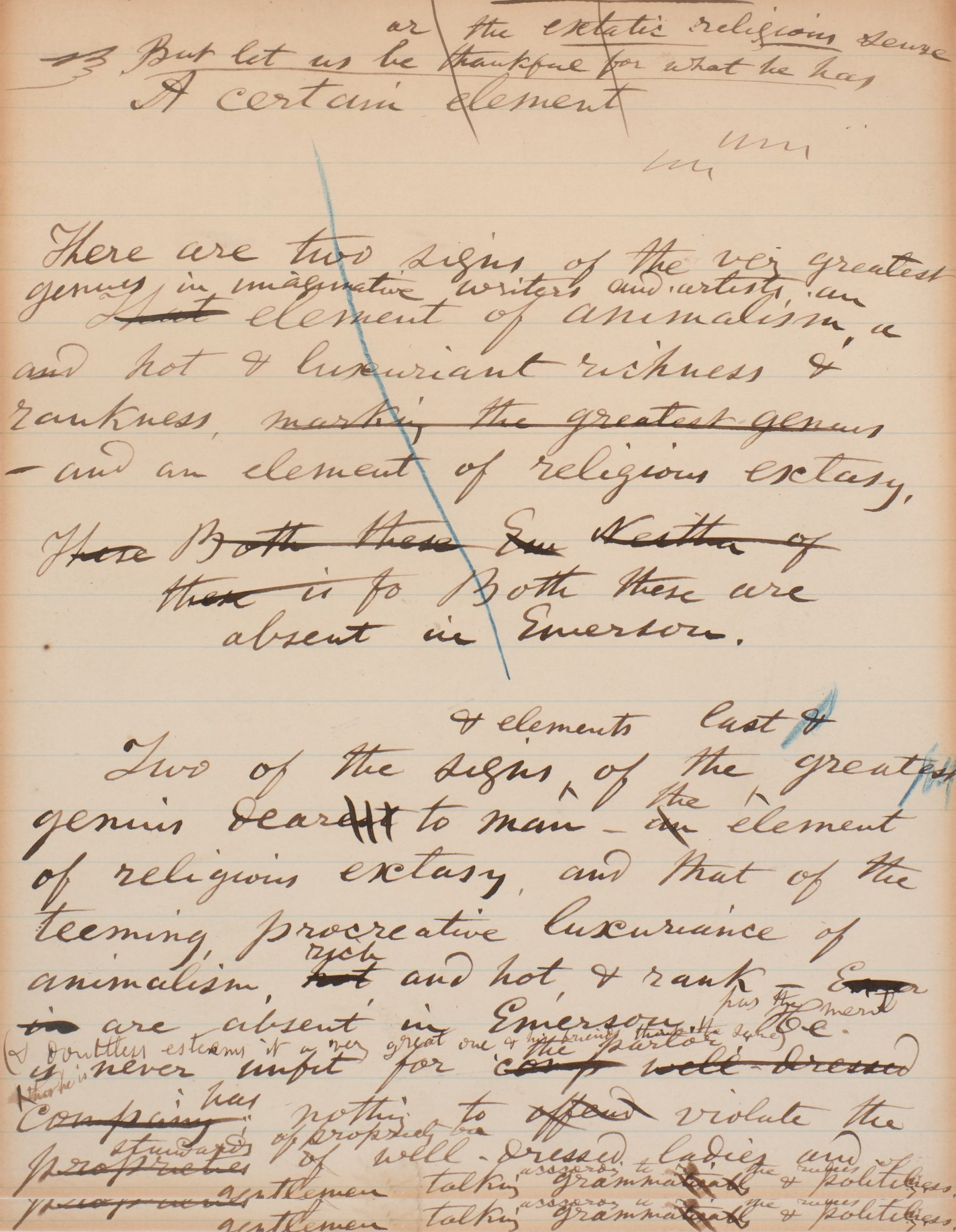

In this fine, heavily revised manuscript Whitman implicitly contrasts his poetry with that of his mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson. Whitman begins by declaring that Emerson “has not the coarse animalism or the ecstatic religious sense. But let us be thankful for what he has …” Those very elements, “coarse animalism” and an “ecstatic religious sense” were two of the elements that Whitman brought to American literature. Whitman continues,

“Two of the signs & elements of the last great genius dear to man—the element of religious ecstasy and that of the teeming, procreative luxuriance of animalism, rich and hot, & rank—are absent in Emerson. He has the merit (& doubtless esteems it a very great one & his friends think the same) that he is never unfit for parlor: he has nothing to violate the standards of properly well-dressed ladies and gentlemen talking according to the rule of grammar and politeness.”

After attending an Emerson lecture in 1842 Whitman appears to have resolved to heed Emerson’s call to greatness. Whitman declared that while he was writing Leaves of Grass in the 1850s, he was “simmering” and that reading Emerson had brought him “to a boil.” When the book appeared in 1855, Emerson hailed it, in a letter to Whitman, as “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. I find incomparable things said incomparably well.” Whitman shared the letter widely, going so far as to print its “I greet you at the beginning of a great career” on the spine of the second edition of Leaves of Grass.

But Emerson soon began to express reservations about Whitman’s poetry, and Whitman in turn cooled on Emerson. This manuscript reflects that change. It may be related to the essay, “Emerson’s Books, (The Shadows of Them),” which appeared in 1880 in the Boston Literary World. In that essay Whitman laid out his concerns about Emerson’s writings. He noted that he once had “Emerson-on-the-brain” and “address’d him in print as ‘master,’ and for a month or so thought of him as such,” but, like “most young people of eager minds,” he was able to “pass through this stage of existence.” He concluded, “The best part of Emersonianism is, it breeds the giant that destroys itself. Who wants to be any man’s mere follower? lurks behind every page. No teacher ever taught, that has so provided for his pupil’s setting up independently—no truer evolutionist.” Whitman himself was that “giant.”

This is an outstanding manuscript contrasting the work of two giants of American literature.

Provenance:

1. John H. Johnston. Johnston (1837–1919) was a New York jeweler and close friend of Whitman. Whitman made several extended stays with the Johnston family in New York in the 1870s and 1880s. This manuscript was likely preserved from one of those visits. In 1888 Whitman told Horace Traubel, “I count [Johnston] as in our inner circle, among the chosen few. Johnston has a transcendental side strongly marked and that’s where he spiritually connects with our crowd: he is free, progressive, alert.”

2. Rev. Arthur Copeland, with a postcard from Johnston to Copeland stating, “Please accept this MSS and photo of Walt Whitman with loving regards of J.H. Johnston.”

$85,000