Whitman on Emerson

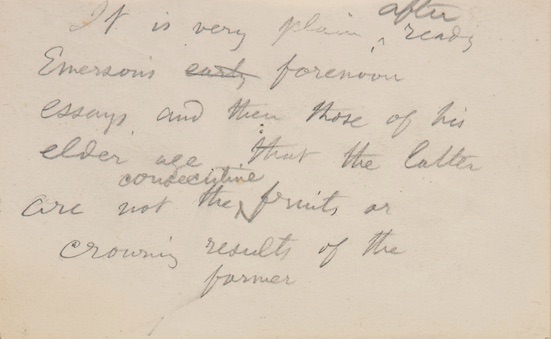

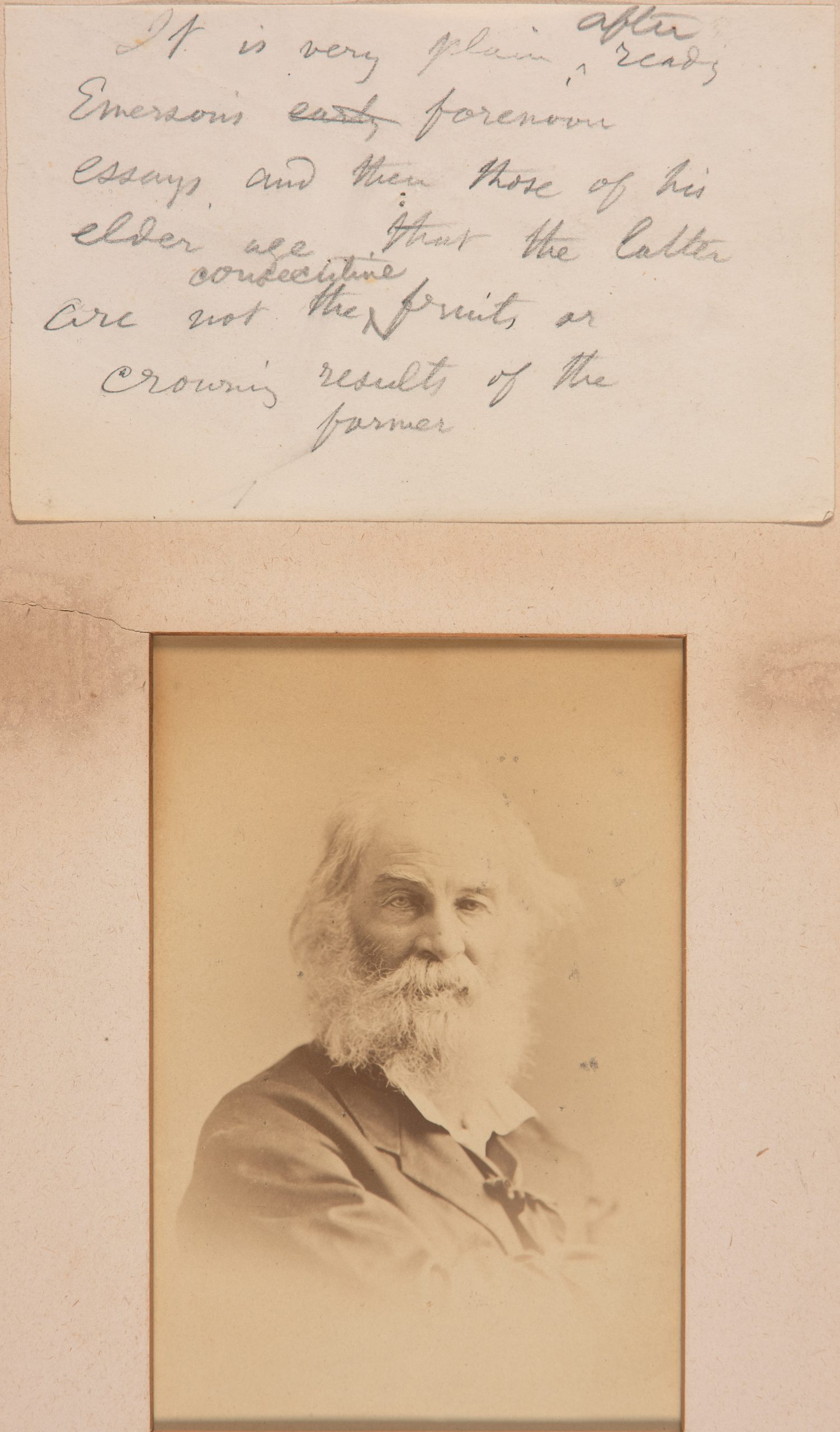

WHITMAN, WALT. Autograph manuscript on Ralph Waldo Emerson

No place, [ca. 1870s]

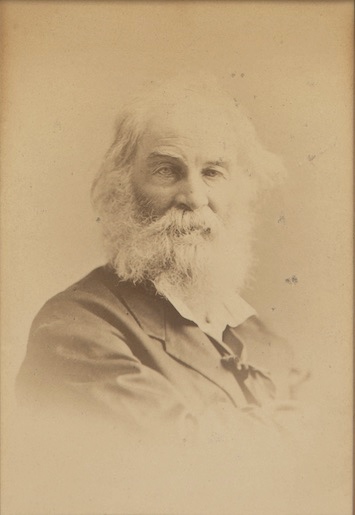

3 3/8 x 5 ½ in. Pencil. Mounted to a mat above an albumen print portrait of Whitman by Rockwood and a card stating in manuscript, “A bit of Walt Whitman MS. From J. H. Johnston New York to His grace, the Archbishop of Canterbury 1904.” Edge wear to mat, manuscript and photograph in very good condition.

[mounted with]

(WHITMAN, WALT.) Rockwood. Portrait of Walt Whitman. ca. 1871. Albumen print (5 ¼ x 3 ½ in.), mounted on card.

In this fine manuscript Whitman writes, “It is very plain after reading Emerson’s early forenoon essays, and then those of his elder age that the latter are not the consecutive fruits or crowning results of the former.”

Whitman declared that while he was writing Leaves of Grass in the 1850s, he was “simmering” and that reading Emerson had brought him “to a boil.” When the book appeared in 1855, Emerson hailed it, in a letter to Whitman, as “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. I find incomparable things said incomparably well.” Whitman shared the letter widely, going so far as to print its “I greet you at the beginning of a great career” on the spine of the second edition of Leaves of Grass.

But Emerson soon began to express reservations about Whitman’s poetry, and Whitman in turn cooled on Emerson. This manuscript reflects that change. It may be related to the essay, “Emerson’s Books, (The Shadows of Them),” which appeared in 1880 in the Boston Literary World. In that essay Whitman laid out his concerns about Emerson’s writings. He noted that he once had “Emerson-on-the-brain” and “address’d him in print as ‘master,’ and for a month or so thought of him as such,” but, like “most young people of eager minds,” he was able to “pass through this stage of existence.” He concluded, “The best part of Emersonianism is, it breeds the giant that destroys itself. Who wants to be any man’s mere follower? lurks behind every page. No teacher ever taught, that has so provided for his pupil’s setting up independently—no truer evolutionist.” Whitman himself was that “giant.”

This is an excellent manuscript linking two giants of American literature.

Provenance:

1. John H. Johnston, with his label on verso. Johnston (1837–1919) was a New York jeweler and close friend of Whitman. Whitman made several extended stays with the Johnston family in New York in the 1870s and 1880s. This manuscript was likely preserved from one of those visits. In 1888 Whitman told Horace Traubel, “I count [Johnston] as in our inner circle, among the chosen few. Johnston has a transcendental side strongly marked and that’s where he spiritually connects with our crowd: he is free, progressive, alert.” Presented to

2. Randall Thomas Davidson, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1903 to 1928, the longest-serving holder of the office since the Reformation and the first to retire from it. On his tour of the United States and Canada in 1904 he was showered with gifts including this representative American literary manuscript.

$28,000