first sex manual in English

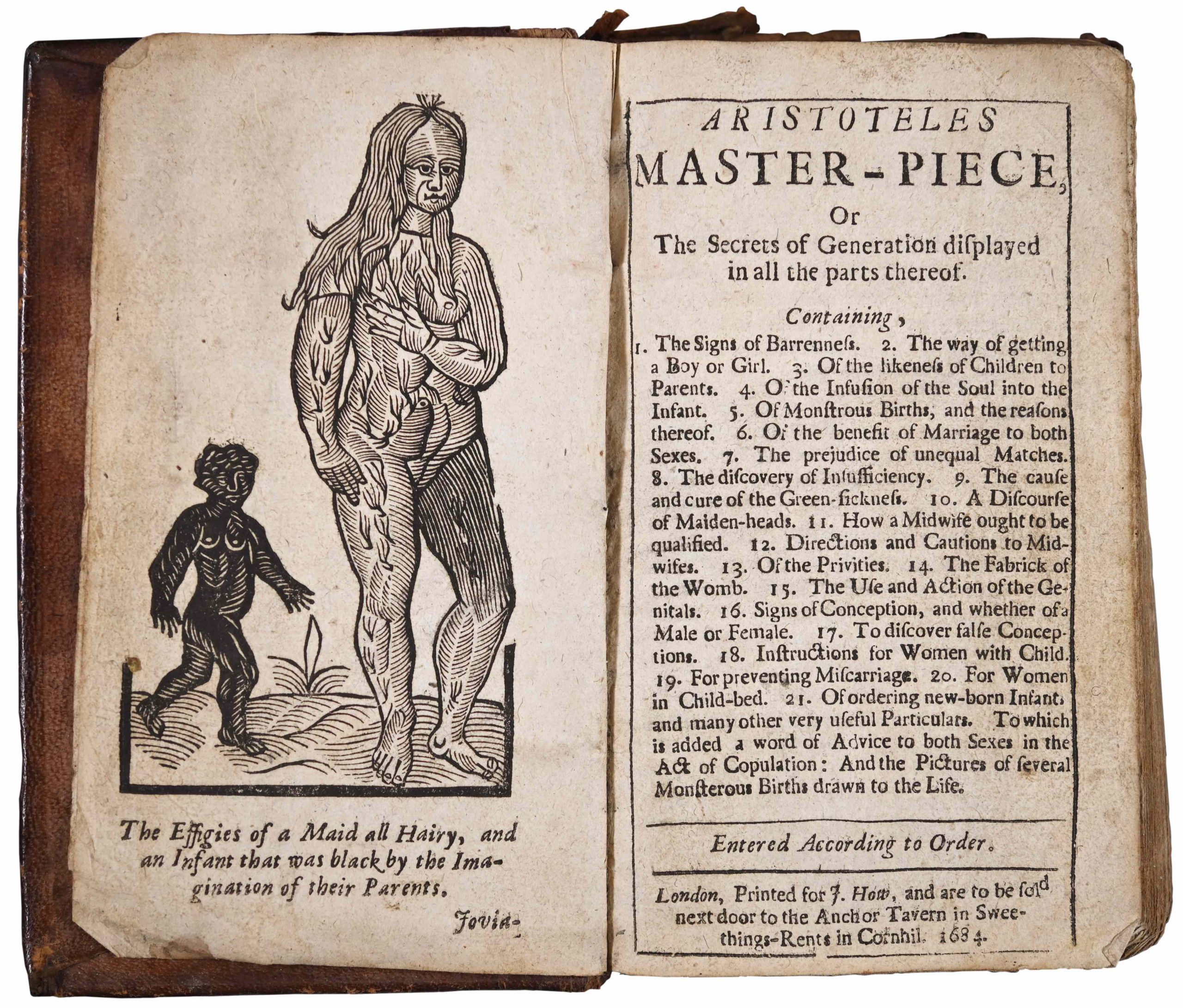

(WOMEN’S HEALTH AND SEX.). Aristoteles Master-piece, or, The Secrets of Generation displayed in all the parts thereof.

London: J. How, 1684

12mo. Contemporary sheep, some wear. Woodcut frontispiece and 6 woodcuts of monstrous births (including repeat of frontispiece). Final gathering well thumbed and dog-eared with short tears at fore-edge with minor losses. A very appealing, honest copy.

First edition of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, “the most popular book about women’s bodies, sex, pregnancy, and childbirth in Britain and America from its first appearance in 1684 up to at least the 1870s” (Treasures, Library Company of Philadelphia).

Aristotle’s Masterpiece—neither by Aristotle nor a masterpiece—is “the first sex manual written in English” (Norman). The work documents theories and practices of human reproduction during the early modern period. This first edition was assembled in part from excerpts of existing midwifery books, primarily Levinus Lemnius’s The Secret Miracles of Nature (1658) and Jacob Rueff’s The Expert Midwife (1658). The book’s pseudo-Aristotle attribution both lent it an aura of credibility and hinted at the sexual nature of its contents. After the publication of a book called Aristotle’s Problems in 1595, which included a few explicit discussions of sex, the name ‘Aristotle’ came to euphemistically indicate sexual knowledge to an early modern audience.

Unlike medical texts on similar subjects, the book was intended for a vernacular readership and was widely disseminated in Britain and America. It was eventually published in hundreds of editions in at least three versions, each appropriating and combining text from existing works. On average, an edition of the Masterpiece was published every year for 250 years. It was still for sale in London’s Soho sex shops as late as the 1930s.

The book’s title page—promising “a word of Advice to both Sexes in the Act of Copulation”—speaks to the sexual knowledge offered within. Aristotle’s Masterpiece emphasizes both male and female partners’ enjoyment of the act. The book’s attention to pleasure was essential to its focus on procreative sex within marriage. Underpinning the Masterpiece is the theory that a woman must “cast forth her Seed to commix with the Man (which imploys a willingness in her to be a Copartner in the Act)” in order to conceive. With female and male partners playing an equally active role in “casting forth their seed,” both partners’ arousal and enjoyment was crucial to reproduction. Thus, women’s sexual appetite was accepted as a natural part of life, and the onset of menstruation credited with “[inciting] their Minds and Imaginations to Venery.” This first edition concludes with “a word of advice to both sexes in the time of copulation,” imparting to its readers a final lesson on the importance of foreplay:

“[A husband] must entertain [his wife] with all kind of dalliance, wanton behaviour, and allurements to Venery but if he perceive her to be slow and more cold, he must cherish, embrace, and tickle her … that she may take fire and be in flames to venery, for so at length the womb will strive and wax fervent with a desire of casting forth its own seed.”

The book’s sexual content gave it transgressive appeal, creating a wider audience than the expectant mothers and married couples for whom it was ostensibly intended. In 1745, minister Jonathan Edwards had to confront teenage boys in his Massachusetts parish after he learned they were reading Aristotle’s Masterpiece and teasing girls with it. Edwards denounced the adolescents from his pulpit; his notes indicate that one boy had a copy hidden under his mattress for several months.

In addition to containing practical advice about sex, pregnancy, and birth, Aristotle’s Masterpiece exhibits a fascination with “monstrous births” and theories of reproduction and resemblance. The frontispiece, depicting a black infant born to white parents and “a Maid all Hairy” testifies to the prevailing theory of maternal imagination; the individuals’ appearances are attributed to their mothers’ thoughts at the moment of conception or during pregnancy. (These mothers had looked at a painting of a black man and prayed to an image of St. John wearing an animal skin, respectively.) Those plates are especially well thumbed in this copy, testifying to the fascination and worry they long engendered.

This is an especially appealing example of a landmark book in the history of women’s health, reproduction, and sex.

The first edition of 1684 is known in three variant settings, all printed by J. How, priority unknown. ESTC records only the incomplete British Library copy (lacking the plates comprising the final gathering I) of our setting, which has line 11 of title ending “both”, line 18 of title ends “Ge-”, and the first line of the imprint ending “sold,” signature B5 is under the “nt Bl” of “effluent Blood” and on p.190 the fifth line from bottom begins with a capital “Q.”

Provenance: “William Sweet [? scuffed] His book 1740 February the 21,” ownership inscription on the verso of frontispiece.

Wing A3697fA. ESTC R504793.

Reference: Mary E. Fissell, “Hairy Women and Naked Truths: Gender and the Politics of Knowledge in Aristotle’s Masterpiece,” in William and Mary Quarterly, Jan 2003.

$60,000